A mental health support worker and video artist acquainted with psychiatrists Jean Oury and Félix Guattari, François Pain filmed persistently at La Borde Clinic, a radical psychiatric hospital founded in 1951 near Paris, and run as a self-organized and non-hierarchical community. His work portrays the place as much as the people who shaped it in the late twentieth century. Diaristic and dialogic, mostly shot spontaneously with a hand-held camera, Pain’s videos came to be precious witnesses of the day-to-day ebullition in this iconic institution and the ethics of life that underline institutional psychotherapy (a post-war psychiatric reform movement that brought together Freudian/Lacanian psychoanalysis and Marxist political theory).

Last May, while in New York with his partner and collaborator Marion Scemama–a filmmaker in her own right, known for her passionate and creative friendship with David Wojnarowicz, and whose films were screened at MoMA this Spring–Pain visited the American Folk Art Museum. Together, Pain and I looked at the ways in which his filmed interviews of Catalan psychiatrist Francesc Tosquelles (conducted with Danielle Sivadon and Jean-Claude Polack in the late 1980s) punctuated the exhibition Francesc Tosquelles: Avant-Garde Psychiatry and the Birth of Art Brut currently on view. An extraordinary archive of a psychiatric revolution that took root in Saint-Alban-sur-Limagnole in Southern France in the 1930s and grew at La Borde Clinic near Paris after WWII, Pain’s images capture Tosquelles’s force of character. It testifies to the complexity of this thinker and practitioner, whose ingenuity is only matched by his unpolished eccentricity.

The exhibition constituted an ideal context to talk with Pain and learn from his first-hand knowledge of a lesser-know, but key, figure of institutional psychotherapy who has only recently received his due. The interview was translated from French and condensed for clarity.

François Pain traveled to New York again last June to present his film LE DIVAN DE FÉLIX and participate in a Q&A session with filmmaker Abdenour Zahzah on Friday, June 21 at Museum of the Moving Image. This screening was part of the film series Radical Institutions and Experimental Psychiatry: The Legacy of Francesc Tosquelles, which took place from June 21 to 23 in conjunction with AFAM’s current exhibition Francesc Tosquelles: Avant-Garde Psychiatry and the Birth of Art Brut, on view through August 18, 2024.

See the full story on MoMI’s Sloan Science and Film website here.

Mathilde Walker-Billaud: How did you get involved in institutional psychotherapy?

François Pain: In 1966, it was my first year studying medicine and I already wanted to focus my studies on psychiatry. I applied for placement in La Borde over the summer. I was accepted and then I stayed there for six years, full- time during weekends and holidays! In the end, La Borde was my real university. It was a place of extraordinary freedom, where we could be whoever we wanted to be… There was a very creative relationship to ‘madness.’ We created workshops in order to do things with the patients. I did a lot of theater; I was in charge of the newspaper La Borde Eclair, and to embellish it, I had created a silk-screen printing workshop. What I learned at La Borde was invaluable: the freedom to think, to create, to be politically engaged where you are (“l’engagement politique là où tu es”) on a micro and institutional basis. The staff at La Borde was very involved in the struggles of the period whether it was the Algerian War, the Vietnam War, or the women’s rights movement.

MWB: How did the medium of film appear in this context?

FP: Film arrived very early at La Borde. As late as the 1950s, René Laloux, who worked at La Borde, produced his first animated cartoon LES DENTS DU SINGE, in collaboration with the clinic’s residents. Numerous documentaries and feature films have also been produced there, both by professionals and amateur filmmakers.

In 1973, I joined the CERFI [Center for Institutional Study, Research and Development] which had contracts with the State, care institutions, and private organizations. The method shared by both the researchers and all the authors was transdisciplinary, and their work was based on institutional analysis. Most of this research was published in the review Recherches.

That year I took a trip to Canada. In Montreal, I discovered the Vidéographe, one of the first centers devoted to lightweight videography, which gave people with film projects, documentary or fiction, access to filming and editing equipment. There I discovered a new piece of equipment: the Sony Portapack, a portable video recorder that we connected to our camera. Lightweight video was born, and with it, a democratic re-appropriation of audio-visual production and distribution methods. It was from this invention that video art developed and took on an international dimension. In Paris, for example, the American Cultural Center and Don Foresta were the driving forces behind the expansion of video in the artistic field. The other advantage of this new technique was that it allowed feedback. The rushes could be shown back to the people who had been filmed.

When I got back to Paris, I suggested setting up a video group at CERFI. We bought some equipment and used video for some of our research. In addition to written notes, we would document the research with filmed elements. We were proposing a mode of reading different from writing.

The same year, I met Jean-Pierre Beauviala, the creator of the Äaton Camera, an extraordinary camera on which he added a small camera capturing in video the footage, so the operator could immediately see what was filmed. I made all my first videos with this camera Paluche which you used like a mic. It was as if I had an eye at the tip of my fingers. It’s the tool with which I made all my first ‘video-art’ films.

MWB: Did you start making films about La Borde at that time too?

FP: There had been a break between my film practice and my psychiatric work. Towards the end of the 1970s I helped set up a video workshop at La Borde, but I was not working there anymore. Then a number of workshops were set up using both video and super-8 films. In 1988, the annual congress of the Croix-Marine [a national gathering for all the psychiatric hospitals’ clubs] was held in Blois, France. Instead of exhibiting objects created by patients–embroidery, pottery, etc–La Borde had decided to show the clinic’s activities through a film. I suggested taking inspiration from a story Fernand Deligny had told me, The Crystal Wave. This text had been created as part of a writing workshop he had run at La Borde. THE CRYSTAL WAVE (1988) was the first film I made within the field of psychiatry.

MWB: In the 1980s, you also filmed the leading practitioners of institutional psychotherapy including Francesc Tosquelles who worked at the Saint-Alban psychiatric hospital during WWII until the early 1960s. What was your impetus to make the documentary about a lesser-known figure?

FP: Tosquelles was one of the central figures of institutional psychotherapy. It was he who best grasped the issues, both political and psychoanalytical, involved in the management and organization of hospitals. He was one of the main figures in the psychiatric revolution that developed in France between the Second World War and the early 1970s. He reinvented psychiatry. He made it a tool that goes beyond the mere reorganization of psychiatry, where politics, psychoanalysis, aesthetics and artistic creation complement each other. It was a way of thinking that appealed to everyone. He took a positive view of “madness.” “If a man isn’t ‘mad,’ then he isn’t anything at all,” he joked once on the radio. “The person we put in a psychiatric hospital is the one who fails his or her madness.” I was lucky enough to have been in analysis with him for four years.

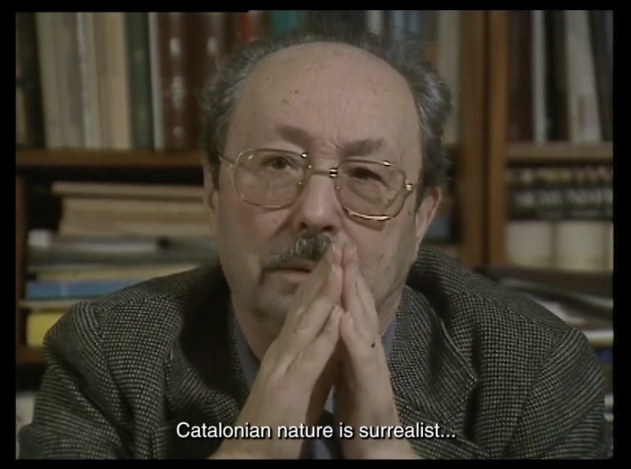

INTERVIEW TOSQUELLES, 1987, film still. Collection François Pain.

MWB: How would you describe Tosquelles’s key contribution to institutional psychotherapy?

FP: The key to describing his contribution to institutional psychotherapy is his own life. Tosquelles’s life is a real adventure novel about a super-talented young man who used his intelligence to improve the way in which ‘madness’ was treated. He began studying medicine at the age of 15 [in Spain]. He soon became involved in unions and political struggles. He joined the POUM [Marxist Unification Workers’ Party] and the Republican ranks against Franco’s regime. In 1937, at the age of 25, he was put in charge of the psychiatric services of the Republican army. During those two years, he pioneered the concept of sector psychiatry (la psychiatrie de secteur), which he organized on the front line “so that patients could be cared for in a place close to the front, where they got into trouble.” Another care model that he set up was therapeutic communities. This technique was widely used at both Saint-Alban and La Borde, and formed the basis of institutional psychotherapy practices.

MWB: Community is at the heart of institutional psychotherapy. Actually, another name for his work at Saint-Alban is “social psychiatry…”

FP: Social psychiatry? You could put it this way, in the sense that the caregivers did everything to bring patients out of their isolation, to increase their opportunities to meet other people, to “socialize.”

And Tosquelles went very far in the socialization of psychiatry, in the “hosting” of the patients [‘l’accueil’ – a term used to designate a listening and inclusive attitude toward the persons living with mental illness]. At Saint-Alban, Tosquelles set up the Club des malades, which managed not only certain activities but also venues. The bar, for example, was run entirely by the patients, as well as printing and other workshops. At La Borde, Oury organized transportation between the clinic and the town of Blois, where there were trains to/from Paris. The car driving service “La Chauffe” was entirely taken care of by the patients–which was something quite exceptional [and officially authorized by the local administration].

MWB: And the caregivers didn’t all come from the medical field.

FP: It was one of institutional psychotherapy’s strong particularities. For Tosquelles, as for Oury, it was not necessary to have only qualified people: nurses, music, or art therapists. What was important was whether or not the caregivers had the capacity to deal with ‘madness.’ It was the same principle at La Borde. I wasn’t a psychiatrist, but I think I did a pretty good job with the patients!

MWB: Can you talk about the making process of the documentary on Tosquelles – what did you all learn from your interview with him?

FP: We wanted to know everything about him: his childhood, his family, his political commitments, why he became a psychiatrist… And we met several characters. He was a Marxist, a bit of an anarchist, a Poumist, a Catalanist but also an internationalist. He was a medical student, a Freudian, a philosopher, a historian, and a great joker… He called psychiatry “deconniatry” [a made-up world combining psychiatry and déconner (fooling around, talking bullshit)]. He co-wrote with philosopher Jacques Ellul La Genèse aujourd’hui (The Book of Genesis Today), the first great Freudian-Marxist book, he said…

MWB: A multifaceted man, with a lot of convictions!

FP: Certainly. Tosquelles was a figure who didn’t back pedal. Even when he was a kid, he took strong positions, with a great sense of humor. Free-spoken, he immediately chose sides, and his position was clear from the beginning of his medical training. He was a Marxist anti-Stalinist. He ended up being condemned to death by the Francists and the Stalinists.

François Pain, FÉLIX’S COUCH, 1985, film still.

MWB: Were psychiatrists at La Borde as politically engaged as Tosquelles ?

FP: Oury was less militant than Tosquelles, but Guattari was political. Actually, Guattari and Tosquelles were a little similar–that’s probably why their relationships often made sparks fly!

To understand La Borde, one must think of Youth Hostels [type of YMCA], where people from the working-class connected to communism were spending their vacation. The group needed to organize to run the house made available to them for several weeks. When Guattari was in charge of the schedule at La Borde, he applied the same principle.

MWB: The famous schedule mentioned in your video LE DIVAN DE FÉLIX (1985)! Guattari confesses that when he was admitted to Saint-Alban (to escape conscription to the Algerian War), he realized that patients were constantly solicited to participate in activities, and this experience had changed his approach to La Borde’s schedule. Your films give us the impression that the practitioners and the patients constantly learn from one another. They reveal a network of interactions, dialogues and friendships inside and outside the hospital. Can you talk about your insistence on the lived experience, your humanist approach to the practice of psychiatry?

FP: It’s because I worked at La Borde. It was important to transmit what I experienced. I also wanted to share what I learnt from Tosquelles as a human being, to transmit what he said. The films are channels of transmission.

MWB: In LE DIVAN DE FÉLIX, Guattari mentions Tosquelles another time, when he speaks with you and Danielle Sivadon about his aesthetical dimension, his dada spirit. This brings us back to the American Folk Art Museum’s current exhibition on the work of this psychiatrist across the fields of experimental psychiatry, communism and surrealism.

FP: Yes, and, as it happens here [in AFAM’s gallery], art is omnipresent. Illness has a creative side, may it be in poetry, in painting, or something else. What I mean is that it has an aesthetic; it’s a sort of aesthetic of life. You know, Saint-Alban, like La Borde, was poor. Some renovations had been made, but it was not a luxury hospital. There was something else–an immense creativity, with the journal meetings, the workshops… We can witness it in the films by Tosquelles, or [Mario] Ruspoli.

MWB: Could we consider Tosquelles as a dada figure, a dada psychiatrist?

FP: Tosquelles was plugged into surrealism. He was himself totally surrealistic. He was like a character coming from the theater, an incredible human being. I liked the way he spoke about surrealism: something more real than the real. [Tosquelles invited us to] push boundaries and go further, but within the confines of the real. It’s important to move toward things that we don’t fully control.