NEW YORK CITY

Artist unidentified

A provocative installation of artworks that span the eighteenth century to the present reveal the remarkable depth and diversity of the museum’s collection. Four universal themes—utility, community, individuality, and symbolism—invite a deeper understanding of folk art and its role in people’s lives.

“Folk Art Revealed” is made possible by leadership support from the Peter Jay Sharp Foundation and major support from the Blanchette Hooker Rockefeller Fund. Additional funding has been provided by The Brown Foundation, Inc., of Houston, the Robert Lehman Foundation, and the Jean Lipman Fellows. Museum exhibitions are supported in part by the Leir Charitable Foundations in memory of Henry J. & Erna D. Leir, the Gerard C. Wertkin Exhibition Fund, and the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs.

The earliest material that we now term folk art was frequently utilitarian in nature, made to meet the basic demands of daily life. Objects such as furniture and household wares received painted and carved embellishments that sometimes served a function—the protection of wood surfaces, for example. These decorations might reflect the transmission of cultural ideas, prevailing trends, and availability of materials. They also visualized the creative desires of their makers and elevated mundane objects into works of art. The idea of utility is often associated with traditional folk art forms, but twentieth- and twenty-first-century works demonstrate the endurance of utility as an impulse for creative expression.

The Comfort of Moses and the Ten Commandments

Richard Dial (b. 1955)

Bessemer, Alabama

1988

Steel and wood with hemp and enamel

57 x 33 x 32 1/2 in.

American Folk Art Museum purchase made possible with grants from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Metropolitan Life Foundation, 1990.3.5

Photo by Brad Wrisley

Richard Dial—part of the creative Dial family of artists from Bessemer, Alabama—is an accomplished metalworker and furniture maker. In 1984, he cofounded Dial Metal Patterns, a small business in metal patio furniture. He learned many of the skills needed to start his entrepreneurial business while working as a machinist at Standard Pullman.

This whimsical and conceptual makeover of an outdoor chair is part of a wrought-iron furniture line Dial calls Shade Tree Comfort. Anthropomorphic, stylized, and full of humor, this line combines utility with Dial’s individualistic decorative flair. The idea behind “shade tree comfort” was to create motifs dealing with comfort and ease, such as “the comfort of the first born” and “the comfort and discomfort of first love,” for example. The understructure of this wrought-iron chair is enhanced by several accessories: a mop imitating a beard and wood and rope creating the stone tablets of the Ten Commandments. Each additive element is a clever detail interpreting the biblical Moses.

Scenic Overmantel

Winthrop Chandler (1747–1790)

Petersham, Massachusetts

c. 1780–1785

Oil on pine panel with beveled edges

American Folk Art Museum, gift of Ralph Esmerian, 2013.1.20

The fireplace was the focal point of most early American homes. By the early decades of the eighteenth century the areas surrounding the hearth began to receive painted embellishments. Chimneypieces, or overmantels, were set directly into the woodwork over a mantel or painted on a separate panel and then wall-hung. These received some of the earliest landscapes painted in America. Sometimes the depictions played a symbolic role, representing the actual properties of a wealthy landowner, or the scene of a significant event in the homeowner’s life. This is one of at least eight overmantels painted by Connecticut artist Winthrop Chandler, who is best known for his imposing portraits of family relations and friends in Connecticut and Massachusetts. Many of his overmantels portray imaginary vistas that nevertheless incorporate typical New England architecture and landscapes, with houses painted in bright colors and window frames and corner boards outlined in white. This example was painted for the artist’s cousin, John Chandler (1742–1794), a wealthy merchant in Petersham. Family tradition maintained that it portrayed London Bridge and the surrounding area before the Great Fire of 1666. However, it is more likely a romanticized view of the Italian city of Florence.

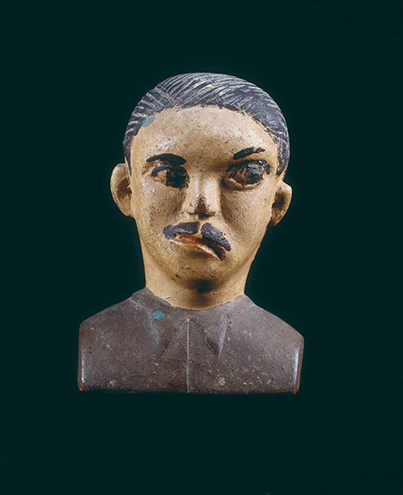

Man with Facial Paralysis

José F. Dos Santos (dates unknown)

Patos, Paraiba, Brazil

c. 1977

Paint on wood

American Folk Art Museum, gift of Roberto Emerson Camera Benjamin Latin American Collection, 1991.4.71

Ex-voto is a Latin term meaning “from a vow.” Ex-votos are a type of Catholic offering to saints in gratitude for the answered prayer of a devotee. Also known as a milagro, or “miracle,” an ex-voto conveys the thanks for an answered prayer and operates as a type of payment for a fulfilled promise. For example, a person who delivered a healthy child might offer an image of a baby at the altar of a saint, or someone who survived a car crash might commission a carving of an automobile, and place that visual prayer at the shrine of another particular saint. A long-standing and universal practice, the making of ex-votos can incorporate silver, gold, brass, wood, bone, plastic, clay, or even wax. Ex-votos come in all shapes and sizes and are crafted at all levels of simplicity or complexity. They are usually made by working artisans as a sideline practice, though many homemade examples also exist.

In Brazil, particularly in the northeast region, ex-votos are usually made of wax or wood. Brazilian ex-votos are additionally interesting because they illustrate the blending of African, native South American, and Catholic traditions common in the northeast; Afro-Brazilians believe that the object actually contains the affliction or the illness and operates as a magical amulet by embodying the affliction. This ex-voto, which is quite distinctive in its painted details, probably was made for someone who survived a stroke.

Anna Gould Crane and Granddaughter Janette

Sheldon Peck (1797–1868)

Aurora, Illinois

c. 1845

Oil on canvas

35 1/2 x 45 1/2 in.

American Folk Art Museum, gift of Ralph Esmerian, 2013.1.18

Before the daguerreotype was introduced into the United States, in 1839, painted portraiture represented the primary means of documenting self and family. Initially, the two methods competed side by side: photography offered an inexpensive, relatively quick, and true-to-life image, while the painted portrait held the weight of tradition and afforded the luxury of large scale and color. The aesthetic of the studio photograph had an effect that is evident in portraits of the Crane family of Aurora, Illinois, by Sheldon Peck. The artist began painting about 1820 in his native Vermont before moving to western New York and then to Illinois. Peck’s earliest efforts were stark and sober bust-length portraits on wooden panels. In Illinois, he introduced a brighter palette and a larger format of full-length figures, as seen in this example. The figures are carefully composed within a stagelike interior with a few well-chosen props—a baize cloth-covered table, an urn of flowers, a Bible. The trompe-l’oeil frame is an added attraction, as the portrait was ready to hang without any further expense. Janette Wilhelmina (1840–1861) is portrayed with her paternal grandmother, Anna Gould Crane (1774–?). According to notes in the family Bible, their portrait was painted on a linen sheet provided by the family and was paid for with the trade of one cow.

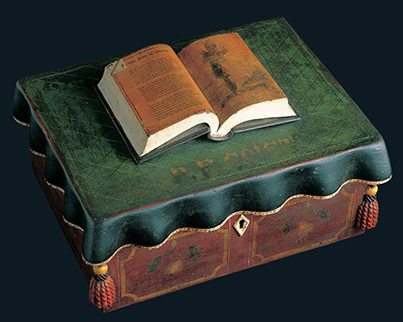

Lectern Box

Artist unidentified

New England

Second half 19th century

Paint on wood with applied printed pages

7 1/2 x 14 1/4 x 10 1/2 in.

American Folk Art Museum, gift of Ralph Esmerian, 2013.1.23

Photo © 2000 John Bigelow Taylor, New York

A sense of playfulness underlies the somber aspect of this trompe-l’oeil box. It can be confidently surmised that it was intended to hold a book, possibly a family Bible. The box simulates a cloth-covered lectern, with heavy tassels at the front corners and a green baize pad on top. A three-dimensional book sits on top of the “lectern” and is opened to a well-thumbed page containing three stanzas of verse. Completing the illusion, the poem is printed on paper and applied to the carved open book. The sensation of surprise and delight provoked by blurring the lines between reality and fantasy continued to be an aspect of the aesthetic of Fancy until it faded from fashion later in the nineteenth century.

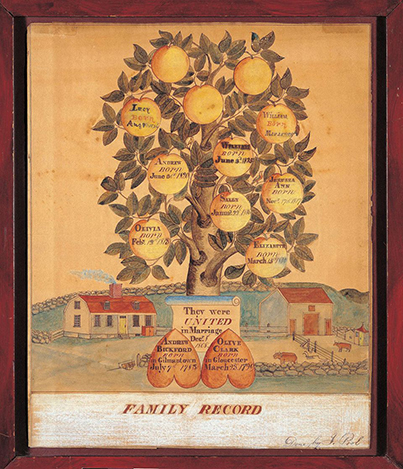

Family Record for Andrew Bickford and Olive Clark

Joshua Pool (1787–?)

Gloucester, Massachusetts

c. 1820

Watercolor, pencil, and ink on paper

15 x 12 in.

American Folk Art Museum, gift of Ralph Esmerian, 1998.17.6

Photo by John Parnell

Family records featuring a tree emerging from twined hearts developed in a defined area of New England, with the greatest concentration in eastern and central Middlesex County, Massachusetts, Cape Ann in eastern Essex County, Massachusetts, and coastal New Hampshire and Connecticut. The majority of needleworks featuring the image were made by female members of the family as students, while the watercolor examples are primarily the work of professional male artists. On Cape Ann, the convention was transmitted through specific family lines and in family records made primarily by Joshua Pool, William Richardson, and William Saville. Of people named in twenty-eight Cape Ann records, only Olive Clark was not a native of the region, further demonstrating the insular nature of the imagery.

The Bickford-Clark record is signed by Joshua Pool, who was probably a resident of Gloucester and possibly a student of William Saville. Olive Clark married Andrew Bickford in 1808 and gave birth to eight children between the years of 1810 and 1828. In addition to vital statistics about their families, this and other decorated Gloucester family records provide a good deal of information about local vernacular architecture. The one-and-a-half story, center-chimney house with gambrel roof is an early form, and its retention as a vital part of this farm shows the generational nature of New England architecture. The property limits are defined by a dry stone wall, which developed in part as a convenient way to use stones unearthed as the soil was tilled. The hand production of family records persisted until the middle of the nineteenth century, when they were largely replaced by printed forms.

A community is not merely a function of proximity in a particular neighborhood. Communities are formed through a variety of circumstances whose common bonds may be of time, place, belief, or experience. In folk art, this is reflected in the wide range of objects that emerge from the shared system that shapes a community. These expressions may point to a common cultural heritage, such as the decorative arts of the Pennsylvania Germans. Some artworks emerge from institutional environments, such as prisons or schools. Still others may indicate a national sense of community and demonstrate an awareness of popular culture or contemporary issues.

Sgrafitto Plate with Horse and Rider

John Neis (1785–1867)

Upper Salford Township, Pennsylvania

1805

Glazed red earthenware

1 3/4 x 12 3/8 in. diam.

American Folk Art Museum, gift of Ralph Esmerian, 2013.1.26

Photo by John Parnell

A number of fine sgraffito-decorated plates similar to this example depicting a galloping horse and rider and with floral or verse-inscribed borders survive from the pottery of John (or Johannes) Neis. Several potters with similar names, some with close family ties, worked in the area of Rockhill and Salford Townships in Bucks and Montgomery Counties during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, and the nature of surviving records and fluctuations in the spelling of their names have confused their identities. The John Neis who created this plate was the son of Henry and Maria Elizabeth Neis of Salford Township; his uncles Abraham and Johannes Neis were also potters. John Neis is thought to have apprenticed with his uncles or with David Spinner, a potter of Swiss descent who was also employed by the elder Neises and whose work shows a close stylistic tie to this plate. John’s sons Abraham and John followed in their father’s and great-uncles’ footsteps and became potters in Montgomery County, continuing operations in the area until the end of the nineteenth century.

Decorated earthenware plates with horse-and-rider motifs and banded inscriptions based on folk proverbs or humorous maxims are found in earlier German and Swiss pottery traditions. In Pennsylvania, the pattern was maintained by immigrant potters, and rather than portraying a particular military figure, such as Emperor Joseph II or George Washington, the figure had likely become a generic, preferred motif. Civic celebrations and local militia exercises with mounted cavalry riders also could have provided inspiration for such figural portrayals. Many of the sgrafitto floral designs executed by Neis have the fluid, confident character of a metal engravimg and utilize similar curved, finely scored parallel lines to delineate the petals of flowers, shading, or the turn of a leaf.

Female Figure Wearing Ghangra

Nek Chand (b. 1924)

Chandigarh, India

c. 1965

Tinted concrete over metal armature

33 x 6 x 6 in.

Photo by August Bandal

American Folk art Museum, gift of the artist with additional support from Charlotte Frank, Kathryn Morrison, Cheryl Rivers, and Steve Simons, 2001.13.2

Begun as a secret landscape project in Chandigarh, India, the Rock Garden by Nek Chand has become a public park for the community. In an act of passive civil disobedience, in the early 1970s, citizens of Chandigarh blocked off Rock Garden and the roads leading to it, denying access to government officials who were intent on destroying it. This community activism virtually saved Chand’s sculptural environment and preserved it as a place where people could visit, relax, and be amused. Now the second-most visited site in India (second to the Taj Mahal), Rock Garden receives government funds, is tended by city workers under the management of Chand, and is an integral part of life for the citizens of Chandigarh.

Much like the United States, India is a country entrenched in class differences and the survival of Rock Garden periodically pits the working class against government officials. Chand began to construct the fantasy environment now known as Rock Garden in 1958, while working as a road inspector in the city of Chandigarh, India. Inspired by the poured-concrete techniques of architect Le Corbusier, who designed the city of Chandigarh, Chand worked in secret in forested public land at the edge of the city. By the 1970s, he had filled his outdoor art installation with figures constructed of concrete and embellished with found materials, including rocks, tile, glass, and paint. Today, with as many as three thousand figures, this remarkable landscape covers more than twenty-five acres.

This sculpture is an early example of Chand’s artwork. Shell is inset into the concrete for facial detailing, and ground-up bricks add red color to the cement material. It was never integrated into the public environment of Rock Garden, but, rather, was made for the artist’s own satisfaction.

Dupatta Mithuna Plaque

Nek Chand (b. 1924)

Chandigarh, India

c. 1965

Tinted concrete over metal armature

33 x 10 x 15 in.

American Folk Art Museum, gift of the artist with additional support from Charlotte Frank, Kathryn Morrison, Cheryl Rivers, and Steve Simons, 2001.13.5

Photo by August Bandal

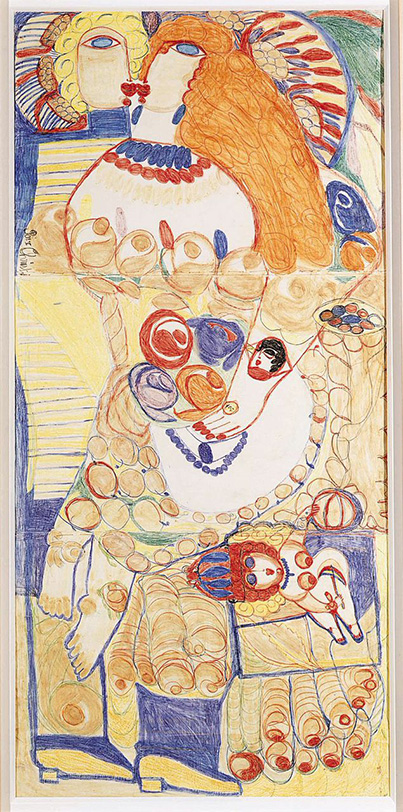

Nenuphars/Paix Christi

Aloise Corbaz (1886–1964)

Switzerland

Mid-20th century

Crayon, colored pencil, geranium-flower juice, and thread on machine-wove paper; double-sided

57 7/8 x 27 5/8 in.

American Folk Art Museum, gift of Etienne Forel and Jacqueline Porret-Forel in honor of Sam and Betsey Farber, 2002.8.1

Photo by Gavin Ashworth

Born in Lausanne, Switzerland, Aloïse Corbaz (1886–1964) moved to Germany before World War I and was employed as a governess for the chaplain of Kaiser Wilhelm II. She began to experience delusions of a romantic relationship with her employer and exhibit an agitated manner and religious fervor, and she was institutionalized in 1918 for schizophrenia. Two years later, Corbaz made her first drawings. She utilized what was available to her in the confined setting but enriched her colorful works with an idiosyncratic assortment of found materials, such as paper packaging, magazine pages, and yarn as well as toothpaste and the juice pressed from flower petals. With these humble materials she created a fanciful world inhabited by kings, queens, dukes, and duchesses. Perspective and proportion are rendered useless in Corbaz’s scroll-like drawings and paintings.

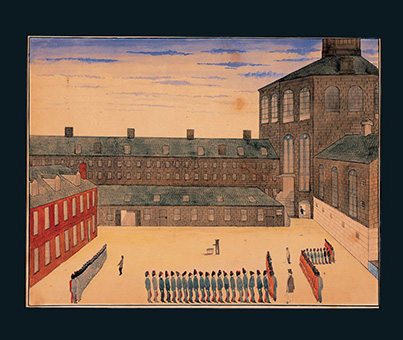

Charlestown Prison

Artist unidentified

Charlestown, Massachusetts

c. 1851

Watercolor, pencil, and ink on paper

15 1/2 x 20 in.

American Folk Art Museum, gift of Ralph Esmerian, 2005.8.12

Photo © 2000 John Bigelow Taylor, New York

Popular notions of community evoke a supportive and industrious network of neighbors with commonly held values and aims. Similarly, strong bonds may be formed through less benign circumstances. Strictures of space, behavior, and activity due to confinement forge an insular community with its own rules, apart from the world at large. This watercolor captures such an example in its depiction of the looming imposition of prison architecture on the regimented lives of its inmates and their proscribed activities within its walls. Before the early nineteenth century Massachusetts had no institutions of confinement that held large numbers of prisoners; punishments were generally meted out on an individual basis. From 1804 to 1805 a secure state prison was built on five acres of land in Charlestown. For the first sixty years in the life of the prison, inmates wore uniforms that were half blue and half red, with painted caps. A yellow stripe was added for repeat offenders, and convicts were tattooed before being released. This was an improvement, though, over previous mutilating punishments, a practice outlawed in Massachusetts about the time the Charlestown prison was built. Originally hailed as a model institution, within its first few years the Massachusetts State Prison in Charlestown became notorious for its cruel conditions.

Noah’s Ark

Artist unidentified

Probably England

1790–1814

Bone and wood with iron, pigment, paper, and nails

8 1/2 x 14 x 9 1/4 in.

American Folk Art Museum, gift of Jane, Steven, and Eric Lang and Jacqueline Loewe Fowler in memory of Robert Lang 1999.14.1

Photo by John Parnell

Noah’s Ark is a prime example of the intriguing bone art of nineteenth-century European prisoners of war. By 1815, after the end of the Napoleonic wars and a series of revolutionary wars that wreaked havoc across Europe, thousands of French seamen (and some Dutch and Americans) were imprisoned in England, some for more than a dozen years. During this period of confinement, friends and family of officers, who generally had privileges greater than those afforded to regular soldiers, were often allowed to supplement the prisons’ inadequate rations of food, clothing, and amenities. For the ordinary seaman, however, bartering became a necessity. Many “ordinary” prisoners came from the French port city of Dieppe, a center of trade with the Ivory Coast that was known for ivory carving and ship modeling. Prisoners with carving skills found a ready market for items created from animal bones recycled from prison kitchens. In addition to bone, the only supplies needed were a knife, a small amount of dye, and glue made from boiled fish bones. Highest in demand were ships of varying sizes made to scale; guillotines, chess sets, boxes, playing cards, sewing implements, and mirror frames also were valued.

Noah’s Ark resembles other works from a prisoner-of-war camp that had been located at Norman Cross, England, some of which are housed in the nearby Peterborough Museum and Art Gallery. This intricate and superbly crafted piece has an ingenious mechanism that resembles that on a carving in the Peterborough collection. Both feature a crank that animates the figures—when the crank onNoah’s Ark is turned, the animal pairs move up a gangplank into the vessel. The elaborate, formal architectural details in the upper portion of the ark, the square tower at the dock, and the windows recall the architecture of the Norman Cross camp, which closed in 1814. Bone carving by prisoners is sometimes confused with scrimshaw, whale skeletal material carved and incised by sailors during long whaling ventures. The two handicrafts are separate, but the are similar in some ways and should be studied in tandem.

Folk art is an effective means of reinforcing conventions, but it also provides a powerful forum for individual expression. At first glance, it may seem to be the work of contemporary self-taught artists that is the most individualistic, even idiosyncratic. However, individuality is found in the personal signature every artist brings to his or her work, even when creating within a conventional form, tradition, or medium. At times this singular voice is expressed through a sense of whimsy or a highly developed aesthetic identity. Other works reveal a distinctive sensibility that is derived from an artist’s strong personal convictions or visions, or from a life lived in isolation.

Animals Appear As Plants—Dwellers of the Sea

Eugene Von Bruenchenhein (1910–1983)

Milwaukee

1956

Paint on corrugated cardboard

21 x 24 in.

American Folk Art Museum, Blanchard-Hill Collection, gift of M. Anne Hill and Edward V. Blanchard Jr., 1998.10.58

Photo by Gavin Ashworth

The son of a sign painter and the stepson of a Sunday painter who believed in reincarnation and evolution, Eugene Von Bruenchenhein was exposed to creative trades and nonconformist ideas from an early age. Before devoting the second half of his life to making art, Von Bruenchenhein worked as a florist and a baker. It was a fortunate foundation for the future artist, who eventually found his voice in a wide range of expressions: photography, painting, ceramics, sculpture, and poetry.

A visionary in every sense of the word, Von Bruenchenhein illustrated his fears of modern war technology and his fascination with other worlds in fantastic, wet-on-wet apocalyptic paintings. He started working on his series of abstract canvases in the mid-1950s, and his subjects are often associated with the threat of nuclear explosions, as well as underwater creatures, perhaps in Von Bruenchenhein’s mind the inhabitants of a post-nuclear-war world. His fantastic imagery is enhanced by his out-of-this-world techniques: Von Bruenchenhein felt free to employ sticks, leaves, crumbled paper, his fingers, and brushes made from his wife’s hair as styluses to apply the paint. He used a jarring combination of colors (secondary colors like green and orange) to great effect, enhancing an otherworldly feeling.

Low Blanket Chest

Artist unidentified

New England

c. 1830

Paint on wood

22 x 41 1/4 x 18 1/2 in.

American Folk Art Museum, gift of the Lipman Family Foundation in honor of Jean and Howard Lipman, 1999.8.7

Photo by Gavin Ashworth

A high degree of individuation can be achieved even when an artisan is working within a prescribed convention. A simple utilitarian form such as this six-board low chest is transformed by the dynamic use of autumnal colors and fanlike patterns to create surfaces that fairly vibrate with energy. The effect is imaginative, rather than that of an attempt to realistically simulate natural wood graining. As such, this abstract surface treatment may be a rural expression of the aesthetic philosophy of Fancy—or imagination—that was popular in the decorative arts of the period. Fantastic and colorful patterns were created through the application of pigment dissolved in water, turpentine, or vinegar, which was then manipulated while wet using a variety of tools or textured materials such as brushes, combs, leather, or putty. In this example, the artist’s hand is literally visible in the repeated pattern of overlapping fans. The technique is traditional, the result unique.

Man Feeding a Bear an Ear of Corn

Artist unidentified

Probably Pennsylvania

c. 1840

Watercolor, ink, and pencil on paper

5 5/8 x 7 1/2 in.

American Folk Art Museum, gift of Ralph Esmerian, 2013.1.37

Photo © 2000 John Bigelow Taylor, New York

Bears and humans have had an ambivalent relationship in North America. The earliest European explorers were not impressed by the American bears they encountered and considered them of little economic value. After the Revolutionary War, however, when there was a compelling need to tame the wilderness and establish communities, the bear took on a frightening aspect as a threat to settlement and a symbol of all that was unknown about the land. There are many possible interpretations of this puzzling but very appealing watercolor. The building, the man, and the chained bear may signify the successful civilization of the frontier. On the other hand, bears have often figured in folktales and other stories because there is something inherently humanlike about them. The man feeding the ear of corn to this bear, who appears small and helpless, may be a twist on an old folktale in which a bear feeds corn to pigs locked in a pen to fatten them up before eating them.

Yet another interpretation of the watercolor may lie in fact rather than fiction. It was not an uncommon practice during the first quarter of the nineteenth century for exotic animals to be put on display to draw customers. While bears could not be considered as exotic as elephants, lions, and camels, they were exhibited in Pennsylvania as attractions outside establishments such as public taverns. In his zoo and museum at Independence Hall in Philadelphia, Charles Willson Peale exhibited two large grizzlies that had been captured by Zebulon Pike. Whatever the actual meaning, the watercolor shares some traits with other Pennsylvania German arts—the tulip and the stars and crescent moon, which may derive from printed almanacs—although they are here expressed idiosyncratically.

Folding Chair

Hosea Hayden (1820–1897)

Union County, Indiana

1883–1896

Horse chestnut with rattan seat

30 x 14 x 20 in.

American Folk Art Museum, gift of Abby and B.H. Friedman, 1996.23.1

Photo by Gavin Ashworth

# Hosea Hayden was an Indiana farmer who used his ready wit, keen observations, and philosophical bent to punctuate the chairs that he crafted for family and friends. Although many of the chairs commemorate specific events, this undated example does not give any clue to Hayden’s incentive for making it. The incised decoration includes an image typical of penmanship exercises of the period, as well as illustrated puns and the sentiment “Mythology the rule, science the exception.” Hayden was descended from English ancestors who immigrated to Massachusetts, fought in the American Revolution, and migrated west to Ohio and Indiana by the early 1800s. His father, Stephen, was one of the original landowners of Union County.

Hayden’s first known chair was made in 1883 to celebrate his father’s one-hundredth birthday; his last was made in 1896, one year before he died. Of the more than a dozen chairs that have been identified, all are folding chairs of Hayden’s original construction and most are tripods. In this example, the chair collapses when the handle is pulled up, much like an artist’s folding easel. Besides their idiosyncratic shapes, the chairs are defined by the philosophical musings and pictures incised into the wood. Based on the inscriptions, Hayden was a freethinker and a rationalist who advocated women’s rights, railed against religious hypocrisy, and satirized popular trends such as women’s fashions.

Espanola

Jon Serl (1894–1993)

San Juan Capistrano, California

1965

Oil on board

26 x 20 in.

American Folk Art Museum, bequest of Gary W. Hager, 1991.31.1

Photo by Gavin Ashworth

Jon Serl’s first hasty attempts at painting were made about the time of World War II. By this point, Serl had already experienced a full life, working in vaudeville, film, and as a laborer in California and the American Southwest. A pacifist, he fled to Canada during both world wars to avoid military service. He was married three times, divorced just as many. Eventually Serl settled in several California towns, including Laguna Beach, San Juan Capistrano, and Lake Elsinore, and devoted his time to painting.

Executed in oil on found surfaces, Serl’s paintings are often brash, bold, and expressionistic. He explored a whole range of techniques with paint and brush; a true painter’s painter, the artist applied paint in a thick impasto as well as in light washes of color. A sensitive use of color, characteristic of Serl’s best artworks, only heightens the drama of his paintings, which abound with characters. The figures that people his paintings often express dualities: male and female, nature and technology, good and evil, parent and child. Often compared to theatrical stages, his canvases usually have an unknown narrative exploring both inner and outer worlds, the emotional as well as the physical.

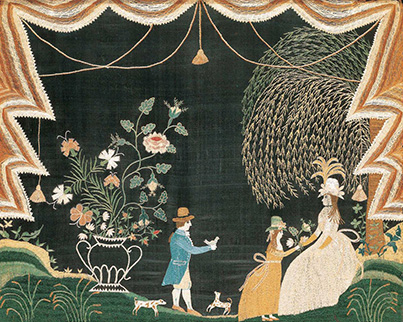

Sallie Hathaway Needlework Picture

Sallie Hathaway (1782–1851)

Probably Massachusetts or New York

c. 1794

Silk on silk

17 x 20 1/4 in.

American Folk Art Museum, gift of Ralph Esmerian, 2013.1.45

Photo courtesy Sotheby’s, New York

Sallie Hathaway’s elegant embroidery on black silk must have brought delight to her parents, for she was their eighth child but the first to survive infancy. Nevertheless, this was an adventurous family. Sallie’s father, John Hathaway (1753–1818), was a mariner of Freetown, Massachusetts, who married Sarah Conkling of Long Island in 1774, but they were in the western Massachusetts town of Great Barrington before Sallie was 2 years old. In 1784, they were among the second group of settlers to arrive in the newly established town of Hudson, New York, where John Hathaway soon became the successful owner of a fleet of ships.

No records reveal where Sallie was educated during the formative years of this port city on the Hudson River. Quite possibly she attended a boarding school in New York City or studied at the recently opened school kept by Miss Betsy Bostwick (1771–1840) in Great Barrington. Bostwick was the oldest daughter of the highly esteemed minister Gideon Bostwick (1742–1793) and Gesie Burghart (1749–1789). Gideon, a Yale graduate of 1762, first settled in Great Barrington as the director of a classical school. In later years, he was ordained and served as minister of the Saint James parish as well as pastor of nearby congregations in New York. The duration of Miss Bostwick’s school is unknown, but she may have been responsible for the exceptional schoolgirl art produced in Great Barrington between 1807 and 1811.

At present, the best-known pictorial embroideries on black silk were worked at unknown schools of Salem, Massachusetts, from the 1740s through the 1770s, and in Boston during the 1750s and 1760s. Black silk was also the most popular ground material for Boston coats of arms during the second half of the eighteenth century. As yet, however, nothing even slightly akin to Sallie’s silk embroidery has been found, and its place of origin remains a mystery.

Sallie Hathaway married Seth Jenkins Jr. (1776–1831), whose father was among the original proprietors of the town of Hudson and its first mayor, and whose family members continued to be leading citizens for a century thereafter. The couple had nine children, and Sallie’s needlework descended in the family of their youngest son, Louis Henry Jenkins (1827–1883).

Some of the most visually potent examples of folk art are those that speak through symbolic language. In these artworks symbols are used as shorthand for revealing complex meanings through graphic representations. The use of symbols can be inclusive, expressing widely recognized ideas and experiences, or exclusionary, as in the arcane symbolic systems of “secret” societies such as the Freemasons. When the symbols pass from common usage or stem from a personal vision, we no longer hold the key to understanding their original meanings. Works become mysterious and subject to new interpretations.

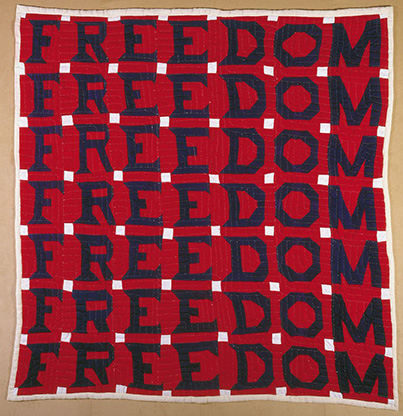

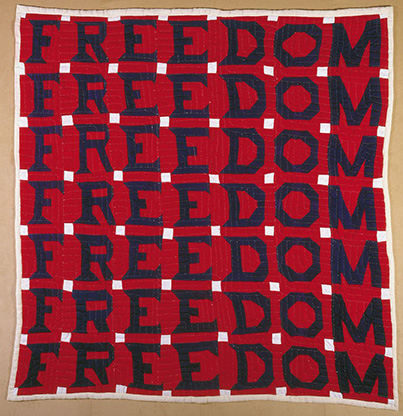

Freedom Quilt

Jessie B. Telfair (1913–1986)

Parrott, Georgia

1983

Cotton with muslin backing and pencil inscription

74 x 68 in.

American Folk Art Museum, gift of Judith Alexander in loving memory of her sister, Rebecca Alexander, 2004.9.1

Photo by Gavin Ashworth

The concept of a freedom quilt can be traced at least as far back as the Civil War, when women were urged to “prick the slave-owner’s conscience” by embroidering antislavery slogans and images into their needlework. Although the existence of Underground Railroad quilts has not been documented except through oral tradition, the idea that quilts were used to encode paths to freedom has persisted into the present. This is one of several freedom quilts that Jessie Telfair made as a response to losing her job after she attempted to register to vote. It evokes the civil rights era through the powerful invocation of one word, “freedom,” formed from bold block letters along a horizontal axis. Mimicking the stripes of the American flag, it is unclear whether the use of red, white, and blue is ironic or patriotic, or both.

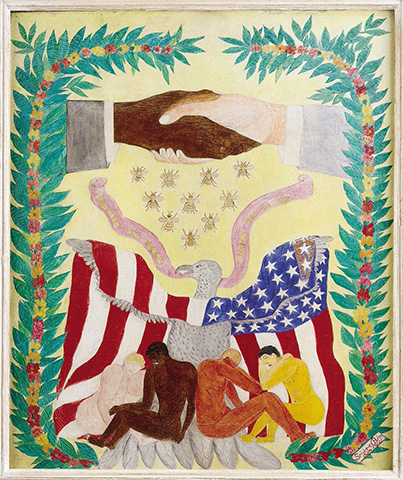

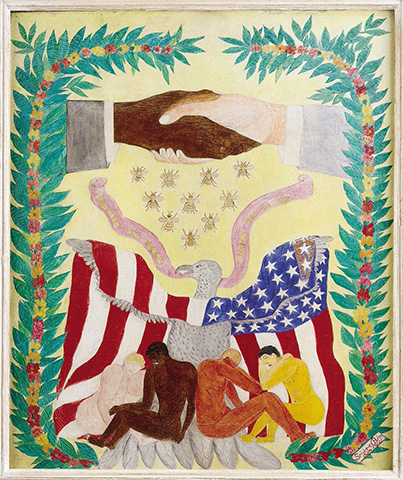

Friendship

Sénèque Obin (1893–1977)

Haiti

c. 1950–1955

Oil on board

20 x 15 in.

American Folk Art Museum, gift of Maurice C. and Patricia L. Thompson, 2003.20.13

Photo by Gavin Ashworth

Haitian self-taught artist Sénèque Obin was instrumental in the success of the Cap-Haitien School of Art. The Obin family—Obin, his brother Philome, and his son Othon—have been prominent figures in this organization, which promoted intuitive artists and introduced their paintings and sculptures to the marketplace.

The longstanding history between Haiti and the United States is complex—an uneasy marriage of assistance with and denial of financial aid, humanitarian aid, and political aid. Political turbulence compounded by ecological disasters and social strife keep twenty-first century Haiti, the only nation to witness a successful slave revolt in the eighteenth century, in peril.

Friendship symbolically illustrates Obin’s hope for a mutually beneficial relationship between the two countries, and thus, too, between the different races of the world. This hope for global reconciliation and friendship is shown by the embracing black and white hands and the intertwined multiracial group of figures at the base of the composition. Both Masonic emblems and Vodun icons are employed by Obin (who was a Mason) in this painting; the use of a flag, an eagle, and decorative flower branches occur in objects from both organizations, illustrating the belief that freemasonry and voodoo are historically connected.

Fame Weathervane

Attributed to E.G. Washburne & Company

New York

c. 1890

Copper and zinc with gold leaf

39 x 35 3/4 x 23 1/2 in.

American Folk Art Museum, gift of Ralph Esmerian, 2005.8.62

Photo by Gavin Ashworth

Weathervanes are used as wind indicators and weather predictors and were of primary importance throughout the nineteenth century, when many occupations were itinerant or otherwise dependent upon outdoor conditions. Historically, they have represented some of the earliest and most significant sculptural forms produced in America. The first weathervanes were usually mounted on churches and other prominent structures within a community, and often had significance as religious symbols. Over time they also functioned as trade signs or ornamental sculptures, with major centers of production in Boston and New York.

This weathervane depicts the Greek goddess and allegorical figure of Fame. She is an ambivalent character whose wreath bestows fame or notoriety and whose trumpet spreads news far and wide. This beautiful example may have been the last weathervane of its type to be manufactured by E.G. Washburne & Company of New York, which was founded by Isaiah Washburn in 1853 at 708 Broadway. In 1907, the operation was moved to 207 Fulton Street, where the Fame Weathervane was installed until 1963.

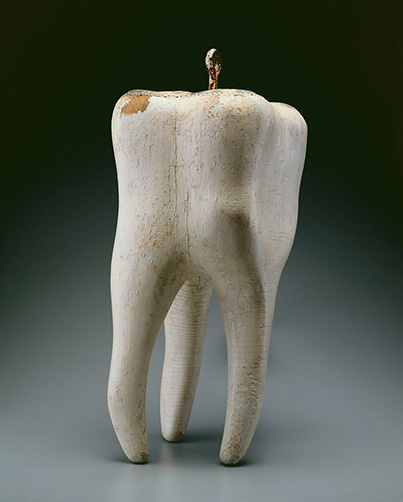

Tooth Trade Sign

Artist unidentified

Probably New England

c. 1850–1880

Paint on wood with metal

26 x 12 1/4 x 11 1/4 in.

American Folk Art Museum, gift of Kristina Barbara Johnson, 1983.8.1

Photo by John Parnell

The most successful early trade sign left little confusion as to its meaning, with or without the use of words. Symbols that were immediately recognizable relied upon a shared system of emblematic meaning, and this interaction between trade sign and viewer still lingers as a traditional method of advertising a business. Some of the earliest signs were flat and painted on both sides, but through the nineteenth century increasingly they were three-dimensional carvings hung off the facade of buildings to catch the eye of passersby. These carved signs were often oversize versions of everyday objects immediately associated with the trade they advertised. Their size helped to draw attention, especially as towns became congested with competing businesses. Many of the early signs established symbols that remain with us to the present time, such as the tooth that was used to advertise the services of a dentist.

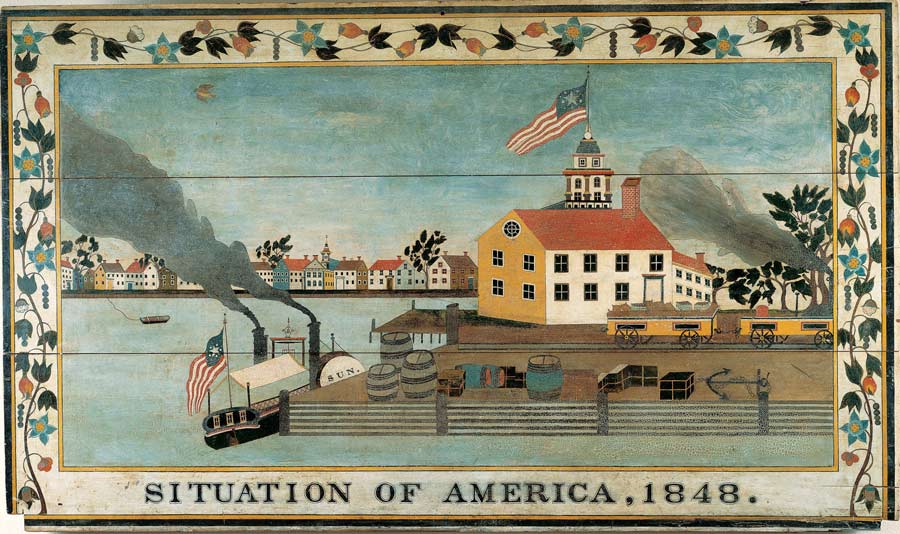

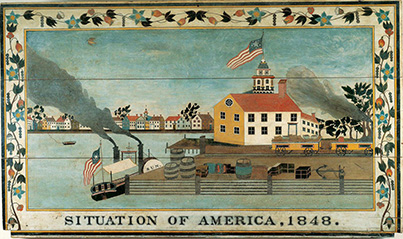

Situation of America, 1848

Artist unidentified

New York

1848

Oil on wood panel

34 x 57 x 1 3/8 in.

American Folk Art Museum, gift of Ralph Esmerian, 2013.1.21

In their letters home, some nineteenth-century visitors to America described how they were struck by the brightness of the climate and the freshness of the paint on colorful houses that lined the streets of cities like New York. This overmantel captures an optimistic and robust picture of the United States as epitomized by New York’s success in mid-century. It celebrates the strong economic ties between consumer and producer, and the means of connecting those markets. Economic growth was greatly spurred by the opening of the Erie Canal in 1825 and subsequent improvements in overland rail transport. A wide variety of goods flooded into New York City along these arteries and were then distributed throughout the country. The architectural muscularity of the skyline as viewed across the East River from Brooklyn is juxtaposed with billows of smoke from the paddle wheeler Sun (built in 1836 with New York as its home port) and the freight train on the wharf. The dome of City Hall looms disproportionately large behind the prominent warehouse situated on the Brooklyn dock.

Celebration

Eddie Arning (1898–1993)

Austin, Texas

1965

Oil pastel on laid paper

21 7/8 x 31 7/8 in.

American Folk Art Museum, gift of Timothy and Pamela Hill, 1981.20.1

Photo by Terry McGinnis

As with many contemporary artists who are self-taught, Eddie Arning’s process usually involved borrowing images from popular culture, such as magazine advertisements, and then distilling the pictorial elements into simple forms and flat shapes. Arning’s sheer joy of repeated pattern, saturated color, and strong design are evident in most of his artworks. The artist transformed the palette of his source, highlighting the bold, rich, generous possibilities inherent in oil pastel and crayons. Celebration is an early drawing by the artist, and it illustrates his intuitive, punchy palette and confident compositional skill.

An art teacher encouraged Eddie Arning to explore drawing in 1964. At the time, Arning was in his 60s and living in a nursing home in Austin, following a thirty-year stay in a mental institution. In this new and nurturing environment, the artist created more than two thousand works of art before stopping, in 1973.

“Folk Art Revealed” is made possible by leadership support from the Peter Jay Sharp Foundation and major support from the Blanchette Hooker Rockefeller Fund. Additional funding has been provided by The Brown Foundation, Inc., of Houston, the Robert Lehman Foundation, and the Jean Lipman Fellows. Museum exhibitions are supported in part by the Leir Charitable Foundations in memory of Henry J. & Erna D. Leir, the Gerard C. Wertkin Exhibition Fund, and the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs.

By Stacy C. Hollander and Brooke Davis Anderson, with Gerard C. Wertkin, Lee Kogan, Cheryl Rivers, and Elizabeth V. Warren; foreword by Gerard C. Wertkin. New York: Harry N. Abrams in association with the American Folk Art Museum, 2001. 431 pages.

By Stacy C. Hollander; with Ralph Esmerian, Helen Kellogg and Steven Kellogg, Lee Kogan, Jack L. Lindsey, Kenneth R. Martin, Charlotte Emans Moore, Betty Ring, Ralph Sessions, Donald R. Walters, Carolyn J. Weekley, Frederick S. Weiser, and Gerard C. Wertkin; foreword by Gerard C. Wertkin. New York: American Folk Art Museum in association with Harry N. Abrams, 2001. 571 pages.