Lady in a Gold-Colored Dress

Ammi Phillips (1788–1865)

The early American republic was a nation of makers. With a lively inventiveness fueled by revolutionary fervor, idealism, and self-taught genius, newly independent Americans filled their lives with art and color. It was widely recognized that the identity emerging from this experimental political system would be judged by “the aggregate formed from the culture of individual minds.” The singular hand of the artist, liberally applied to practical needs such as portraits, pottery, furniture, textiles, documents, and trade signs, helped to unify a culturally and economically diverse populace. Artmaking was already something of a national habit before the first museums were established in the United States, and developed along diverging tracks: the work of self-taught practitioners that was enjoyed primarily in personal or local settings, and elite art that was measured against a European standard and intended to prove America’s earned status in world culture. Together they comprised a sort of national “wonder cabinet,” a snapshot of American society at large.

Self-taught artists were part of a story that was daily unfolding, yet their names were often not recorded and were therefore excluded from documented history. The slow recovery of their identities, and a renewed appreciation of their art, owes its greatest debt to two forces that aligned in the early years of the twentieth century: Colonial Revival and Modernism. The first grew out of an interest to document and preserve an American narrative firmly rooted in the colonial past. The second sought to legitimize a radical artistic movement through a visual legacy that was uniquely American. The field of American folk art that coalesced around these two poles reclaimed the original context of the art as a vital part of life, a rich complex built from the culture of individual minds.

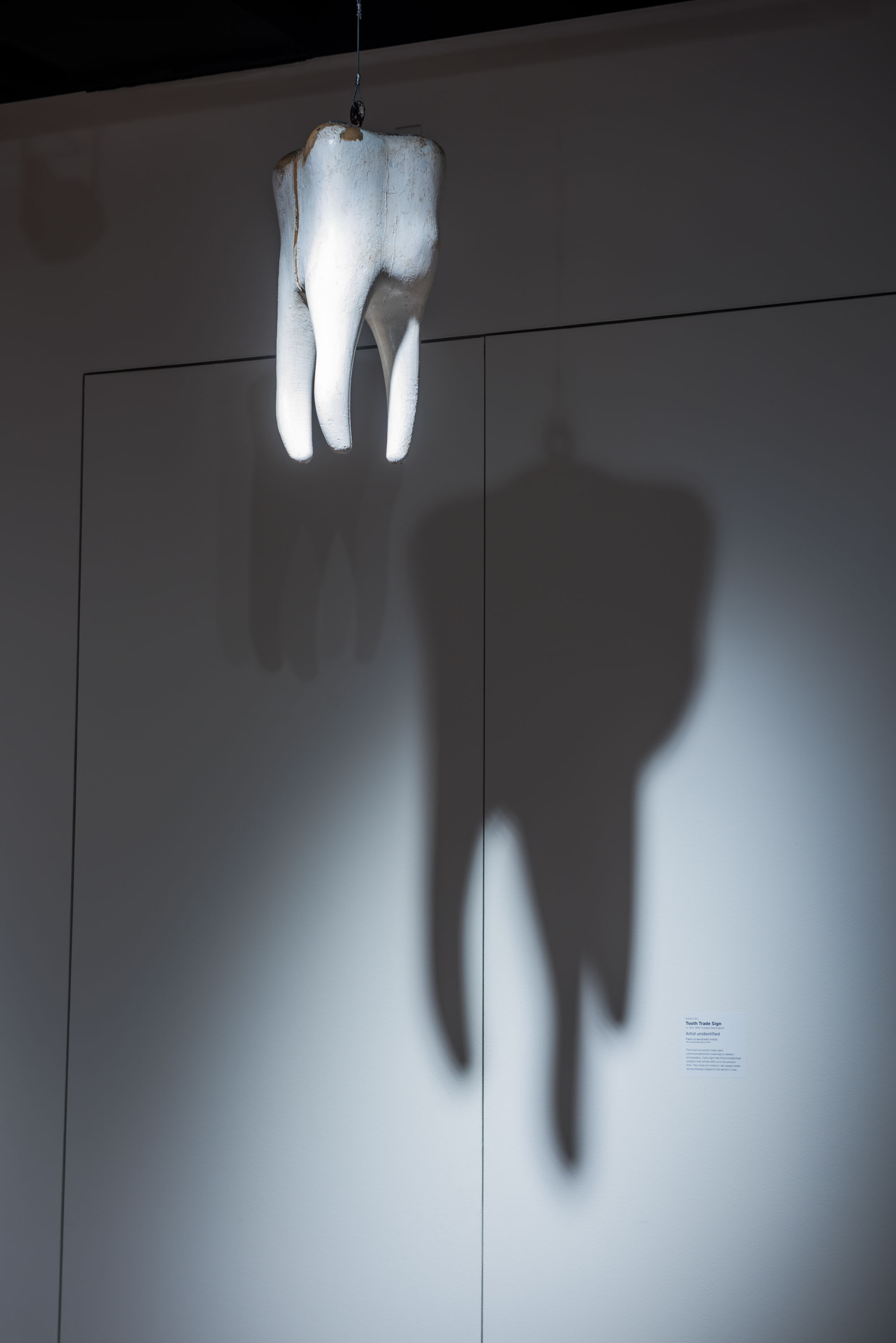

Images, left to right:

Lady in a Gold-Colored Dress, Ammi Phillips (1788–1865), probably New York, Connecticut, or Massachusetts, 1835–1840, oil on canvas, 40 1/2 x 35 3/4 x 2 7/8″ (framed), American Folk Art Museum, gift of Joan and Victor Johnson, 1991.30.1. Photo by Gavin Ashworth.

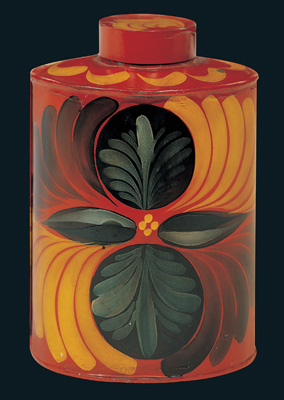

Oval Tea Canister, artist unidentified, Pennsylvania, c. 1825–1850, paint on tinplate, 5 1/8 x 3 9/16 x 2 3/4″, American Folk Art Museum, gift of the Historical Society of Early American Decoration, 76.1.7.

Slashed Star Quilt, Sara Maartz (dates unknown), Lancaster, Pennsylvania, dated 1872, cotton, 82 x 76″, American Folk Art Museum, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Alan Weinstein, 2007.15.1. Photo by Gavin Ashworth.

Tall Case Clock, artist unidentified, clockworks attributed to Lambert W. Lewis (c. 1785–1834), Trumball County, Ohio, 1812–1834, paint on pine case, with watercolor on paper clockface and wooden clockworks, 87 x 21 1/2 x 12 3/4″, American Folk Art Museum, museum purchase, Eva and Morris Feld Folk Art Acquisition Fund, 1981.12.22. Photo by John Parnell.

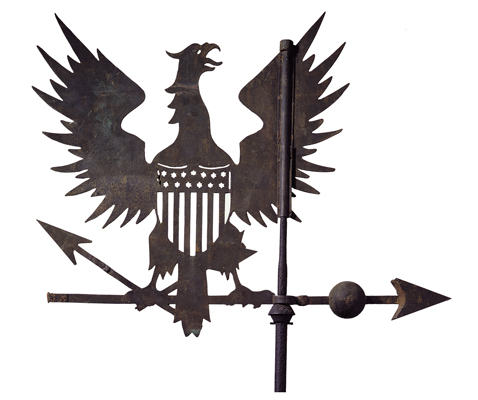

Eagle and Shield Weathervane, artist unidentified, Massachusetts, c. 1800, cast bell metal, 36 x 43 1/2 x 4″, American Folk Art Museum, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Francis Andrews, 1982.6.4. Photo by John Parnell.

Interior of John Leavitt’s Tavern, Joseph Warren Leavitt (1804–1833), Chichester, New Hampshire, c. 1825, watercolor, ink, and pencil on paper, in original maple frame, 8 9/16 x 10 1/2 x 1/2″ (framed), American Folk Art Museum, gift of Ralph Esmerian, 2005.8.5. Photo © 2000 John Bigelow Taylor, New York.

Sallie Hathaway Needlework Picture, Sallie Hathaway (1782–1851), probably Massachusetts or New York, c. 1794, silk on silk, 17 x 20 1/4″, American Folk Art Museum, gift of Ralph Esmerian, 2013.1.45. Photo courtesy Sotheby’s.

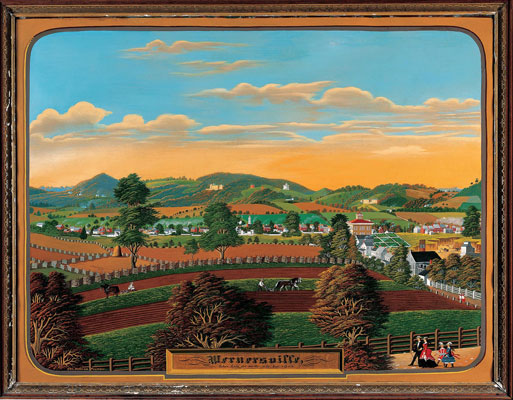

Wernersville, Taken from the North-Side, Charles C. Hofmann (1821–1882), Berks County, Pennsylvania, 1879, oil on zinc-plated tin, 32 1/8 x 40 3/16 x 2″ (framed), American Folk Art Museum, gift of Ralph Esmerian, 2005.8.14. Photo © 2000 John Bigelow Taylor, New York.

Carousel Horse with Lowered Head, Charles Carmel (1865–1931), Coney Island, Brooklyn, New York, c. 1914, paint on wood with glass eyes and horsehair, 58 5/8 x 63 x 14 7/8″, American Folk Art Museum, gift of Laura Harding, 1978.18.1. Photo by John Parnell.

Installation photography courtesy of Stephen Ironside. Watch a short video tour of the exhibition below, narrated by Chief Curator Stacy C. Hollander, and edited by Adair Creative.

Curated by Stacy C. Hollander, Deputy Director of Curatorial Affairs, Chief Curator, and Director of Exhibitions. The exhibition is organized by the American Folk Art Museum in collaboration with Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art.

Curated by Stacy C. Hollander, Deputy Director of Curatorial Affairs, Chief Curator, and Director of Exhibitions. The exhibition is organized by the American Folk Art Museum in collaboration with Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art.