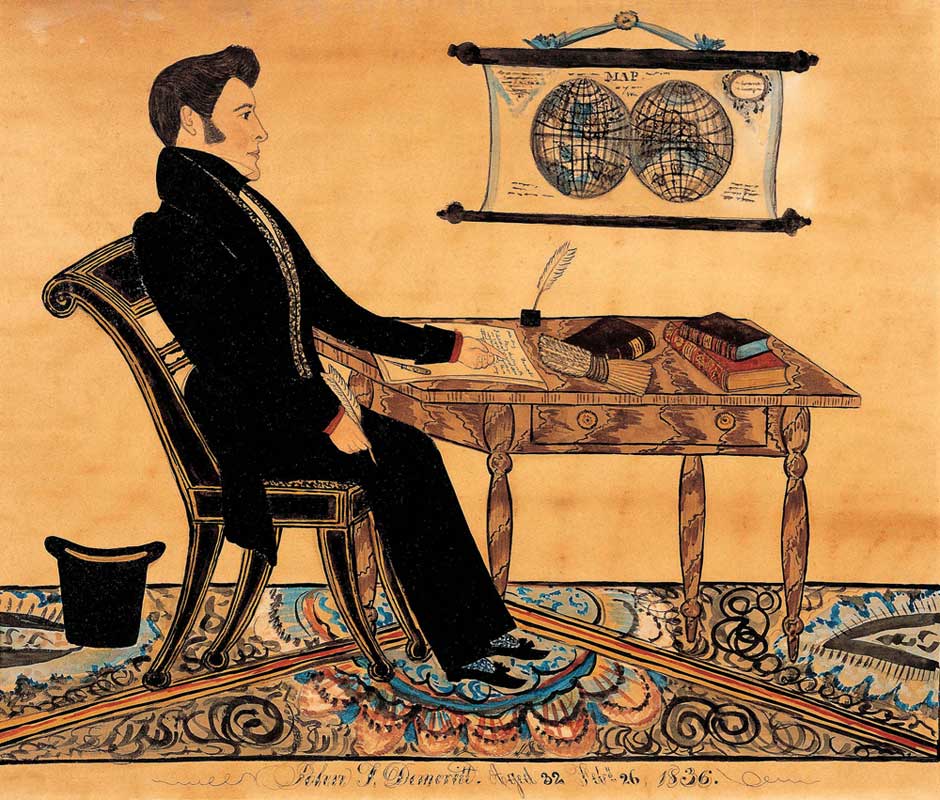

John F. Demeritt

Joseph H. Davis (act. 1832–1837)

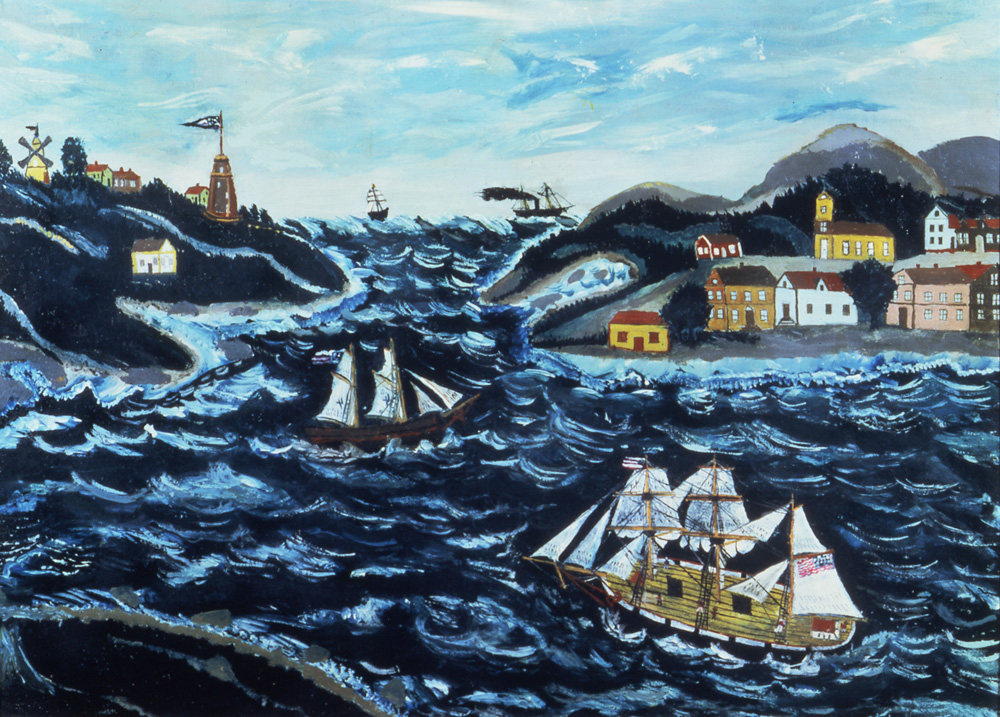

New York City has a rich history largely tied to its thriving harbor activities and developing urban environment. The American Folk Art Museum responds to this context through a lively sampling of artworks from the collection that speaks to both the romanticism and gritty realism of the seaport district. The exhibition “Compass: Folk Art in Four Directions” is installed in four galleries of Schermerhorn Row, the mercantile block that was developed between 1810 and 1812 by Peter Schermerhorn, scion of a family of shipmasters and chandlers. Six counting houses were built on landfill with the intention of serving the ship trade, the market economy, and compatible small business of the time. Throughout its history the Row experienced and survived the major expansion of the seaport district in both architecture and importance as a major trading and commercial center. The Row housed various concerns through the nineteenth century, including counting houses, mercantile and fancy goods businesses, coffeehouses, restaurants, and hotels for locals and travelers. The American Folk Art Museum celebrates this history through four themes that instigate a visual dialogue about moments in the life of Schermerhorn Row and the seaport.

In the early years of the seaport district, the world was still a vast enigma, and tales of far-off places stirred the imagination. Commercial expeditions yielded exotic goods while ordinary seamen were granted opportunities to experience customs and landscapes very different from their own. Exploration delves into the perils and rewards of lengthy voyages, the urge to explore, and the yearning for loved ones left on shore. Social Networking reflects on the Row’s history as a coffeehouse and inn. Social networking was part of the coffeehouse scene from its earliest origins, providing the perfect nexus for business and social interactions, as well as solitary musings over a cup of coffee. Shopping focuses on the wealth of staple and fancy wares that were available in this thriving commercial district with shops, open markets, and diverse activities aimed at both traveler and local. The exhibition concludes with Wind, Water & Weather, artworks that respond to environmental aspects of the seaport: images of seagoing vessels and harbor activities, weathervanes that indicated wind direction, and outdoor trade carvings that show the effects of weathering by the elements.

Sea Captain

Attributed to Sturtevant J. Hamblin (act. 1837–1856)

Probably Massachusetts

c. 1845

Oil on canvas

27 1/8 x 22 1/4 in.

American Folk Art Museum, gift of Robert Bishop, 1992.10.2

Photo by John Parnell, New York

Portraits of sea captains are poignant reminders of the hazards and hardships posed by the oceangoing trades during the nineteenth century. Perhaps more than any other single community, men who followed the seafaring professions relied on painted portraits to function as a surrogate presence in their homes, as voyages frequently lasted years and men did not always survive to return home. This is one of several similar portraits of sea captains painted by Sturtevant J. Hamblin, who established himself in Boston with his brother-in-law, William Matthew Prior. The two were the primary practitioners of a schematic style of portraiture “without shade” that could be completed quickly and at modest cost to the client.

John F. Demeritt

Joseph H. Davis (act. 1832–1837)

Probably Barrington, New Hampshire

1836

Watercolor, pencil, and ink on paper

9 11/16 x 11 in. (sight)

Private collection

The schoolmaster was an important member of a community. In district or common schools, it was customary for the teacher to be a young man during the winter months and a woman during the summer, when farming and other occupations may have taken precedence. According to his obituary in the Freewill Baptist organ The Morningstar, John F. Demeritt “devoted his early life to teaching common schools and always manifested a deep interest in the education of the young in his vicinity.” Geography was clearly part of this education as indicated in this drawing. In addition to map study, teaching geography to young girls might involve “working maps” as part of the regular curriculum.

Cane with Female Leg Handle and Cane with Female Leg and Dark Boot Handle

Artists unidentified

Probably eastern United States

c. 1860

Whale ivory and whale skeletal bone with horn, ink and nail (left); whale skeletal bone, mahogany, and ivory with paint (right)

29 3/4 x 3 1/2 in. (left); 34 x 3 3/4 in. (right)

Private collection

Photo © 2000 John Bigelow Taylor, New York

The art of scrimshaw—embellished keepsakes made from organic materials derived from whales and other marine mammals—is largely a by-product of the American whaling industry. Operating from such ports as Nantucket, New Bedford, and Sag Harbor, whaling flourished from about 1830 through the early twentieth century. Making scrimshaw helped to fill time and deflect the complex emotional dynamics that characterized male crews confined onboard ship for long periods of time. The act of carving also enabled sailors to maintain an emotional link to loved ones on distant shores by fashioning various tokens as gifts. Beginning scrimshanders started with a simple project like a plain walking stick and moved on to more ambitious work as their skill increased.

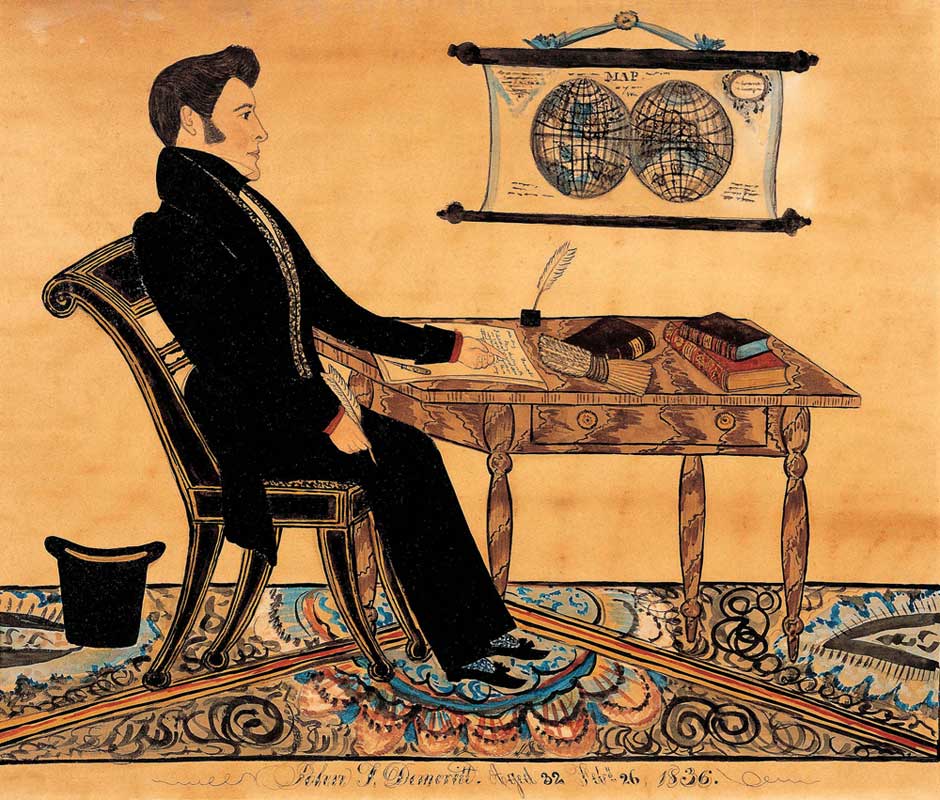

At Jullo Callio. And again escape and being persued by wild Glandelinian soldiery suddenly dash into a party of Christian soldiery and are rescued. (double sided)

Henry Darger (1892–1973)

Chicago

Mid-20th century

Watercolor, pencil, and carbon tracing on pieced paper

19 x 47 3/4 in.

American Folk Art Museum purchase, 2002.22.1a

© Kiyoko Lerner; photo by James Prinz

The Chicago artist Henry Darger led a very private existence. The full breadth of his work was discovered only after his death by his Chicago landlord, artist and industrial designer Nathan Lerner. Darger is best known today for around 300 single-sheet and panoramic multi-sheet watercolors related to his writings, notably the 15,000-page epic, The Story of the Vivian Girls, in What Is Known as the Realms of the Unreal, of the Glandeco-Angelinnian War Storm, Caused by the Child Slave Rebellion. After the death of his mother, Darger was relegated to a notorious Illinois asylum for children. The depredations of the institution left an indelible mark on the sensitive boy and he escaped in 1908. During his journey by foot back to Chicago, Darger experienced a terrifying tornado. This formed the basis for a fictionalized account of a twister named “Sweetie Pie” that occupies more than 4,000 pages in a written narrative. The watercolors included in the exhibition depict extreme weather conditions that continued to occupy Darger: lightning strikes, storm clouds, wind, and rain.

E. Fitts Jr. Store and Coffeehouse Trade Sign

Artist unidentified

Vicinity of Shelburne, Massachusetts

1832

Paint on wood with wrought iron

22 3/8 x 34 1/2 in.

American Folk Art Museum, gift of Margery and Harry Kahn, 1981.12.9

Photo by John Parnell, New York

Coffee, tea, and chocolate were introduced into England by the late seventeenth century, and coffeehouses quickly became centers of social and business interaction. By the eighteenth century, these establishments were imitated in America, where they offered current newspapers, magazines, and pamphlets and served as meeting places for social, political, military, religious, and secular activities. E. Fitts Jr. has not been identified, but his painted trade sign indicates the coffeehouse on one side and his store on the other. In addition to a large stock of hats, reams of fabric, and dry goods, the store may have offered some food or drink, as there are barrels stacked on one side and the shelves have a variety of pottery vessels.

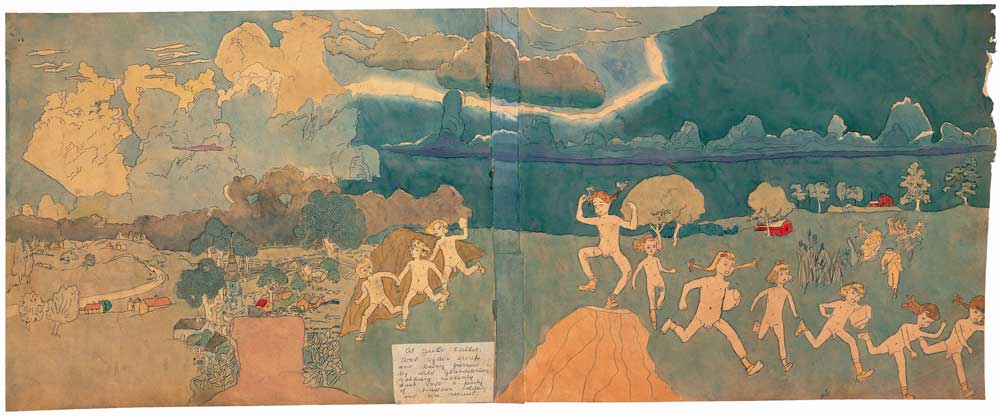

Harbor Scene on Cape Cod

Artist unidentified

Massachusetts

1890–1900

Oil on canvas

23 x 31 3/4 in.

American Folk Art Museum, gift of Robert Bishop, 1992.10.11